In the previous article, we looked at including Test Cases and the Functional Risk Assessment into the Functional Requirements Specification. This provided multiple benefits over maintaining these as separate documents:

- Forces requirements to be testable (described in the test cases)

- Forces thinking using ‘what if’ scenarios on requirements which leads to test cases and enhanced requirements (i.e. verification of control measures)

- Justifies the documentation required for each test case (by using the risk level to determine test documentation effort)

- Provides the documentation framework to record Performance Qualification (PQ) / User Acceptance Testing (UAT)

- Removes the need for a Traceability Matrix from requirements to testing (self-contained)

- Raises the likelihood that requirements documents are kept current with test documentation

In this article we will take a more detailed look at how the functional risk levels can be used with vendor supplied, configured and customised software to justify less documentation, and in some low risk cases, less testing at the System / Operational Qualification (OQ) level.

Note that software functionality per requirement can be achieved in three ways:

- Out of the Box – The software satisfies the requirement without any change

- Configured – The software requires some level of configuration to satisfy the requirement

- Customised – The software requires some level of scripting or coding to satisfy the requirement

There can be some debate over what is ‘configured’ and what is ‘customised’, and in some instances, it can be a little ‘grey’.

If you are changing a software product within the boundaries of what the vendor has anticipated, then you are probably configuring.

If you are changing a software product outside the boundaries of the base product (either by script or code) then you are probably customising.

Some products are supplied with the ability to customise them via an Application Programming Interface (API) that allows access to the base building blocks used to create the solution to satisfy the requirements.

Separate products or programming tools can also be used to provide additional functionality to a base product to satisfy functionality not explicitly available in the base product.

By passing down the Functional Risk level into the design / configuration specification or user manual (against the relevant design / configuration element) and then assessing how that requirement is achieved (i.e. Out of the Box, Configured or Customised), decisions can be made as to the level of test documentation required at the System / OQ level.

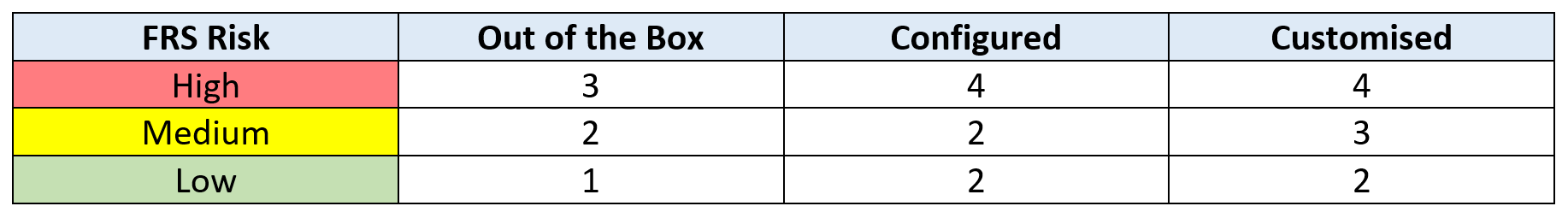

The table and recommended test documentation below can be applied to each requirement:

4 – Detailed Script (in the format that most companies currently write their Test Scripts)

3 – Limited Script (sign off, perhaps with some instructions / attachment)

2 – Test Case (Unscripted test) with confirmation only

1 – Witness but no documentation, confirmed in PQ/UAT

From this table, we can see that detailed test scripts would only be required for configured or customised high risk functional requirements.

Some limited test scripts would be required for Out of the Box high risk requirements and medium risk customised requirements.

Low risk Out of the Box requirements would require no documentation at all (as these would be witnessed and confirmed as part of PQ / UAT) and all other requirements would simply require witnessing and confirming.

All System / OQ testing performed, and knowledge gained, could be used to update the risk level in the Functional Requirements Specification; and hence, reduce the test documentation required there.

If little to no formal testing (based on this risk and product configuration knowledge) is performed during the System / OQ exercise, or the vendor has little to no documented evidence of their testing of the base software, then there will be more higher risk level requirements in the PQ / UAT. This will lead to a more detailed test effort by the end users.

However, if the vendor does have evidence of base software testing, then this, together with sufficient confirmation of coding / configuration of the final solution can greatly reduce the documentation effort during the PQ / UAT testing.

From the closed loop above you can see that Computer Software Assurance (CSA) can be summed up as ‘Risk Based Documentation’ rather than ‘Risk Based Testing’ as it still ensures that functioning requirements are at least witnessed at some point in the process.

The key is to encourage critical thinking to learn more about both the process and the computer system during the design and development phases, which leads to justification for minimising unwarranted and duplicate documentation during the testing phases.

As well as the benefit of producing less documentation, a more easily maintainable set of documents can be produced which assists with ongoing maintenance and future upgrades / changes.

SeerPharma has successfully used the CSA approach and is helping companies to move towards this less burdensome approach to Computer Software Assurance.

Contact us if you would like to know more about CSA, and how these proposed changes may affect your organisation.

Interested to read more on CSA? Please review our previous articles in this series:- Article 1 : Computer Software Assurance

- Article 2: Computer Software Assurance - Risk and Reward

- Article 3: Computer Software Assurance - Use of Critical Thinking

- Article 4: Computer Software Assurance - Configuration / Design and Closing the Loop (this article)